Two hundred years ago London was a filthy, stinking place. Its rapidly expanding population was putting huge strain on the capital’s resources. The city at the heart of an empire was growing economically too, but with affluence came effluent. The way Londoners traditionally disposed of their waste was primitive in the extreme. Rivers such as The Fleet were used as open drains and the water from them flowed untreated into Father Thames. Before water closets most homes had outside privies that leached tainted water into the water sources. The muck from public latrines was collected in open carts to be dumped in the river. To make matters worse the streets were often unpaved, muddy and covered in horse manure.

Bodies were still buried in shallow graves in London’s churchyards and as they decomposed they too contaminated the water supply.

In the first decades of the 19th century London was urgently in need of a major clean up. One of the first reformers to face up to the task was Edwin Chadwick who saw poverty and poor sanitation as being two closely connected issues. His pioneering report of 1842 ‘The Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Population’ set in train a range of important improvements. He was also responsible for new legislation requiring bodies to be disposed of in a decent and hygienic manner.

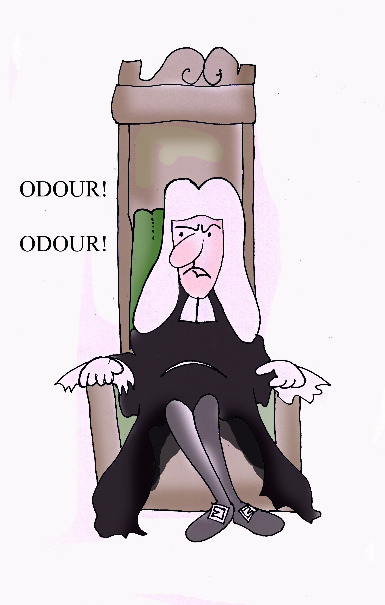

But London did not improve overnight. Indeed as the population continued to grow some problems became even more acute. By 1858, the stench rising from the River Thames was so bad that MPs seriously considered moving parliament from Westminster to Oxford or St Albans. The river was little better than an open sewer running through the middle of the capital. ‘One of the noblest of rivers has been turned into a cesspool,’ one MP told the House of Commons. Dickens novel ‘Our Mutual Friend’ opens with a description of a boatman who made a living by finding corpses in the river that he then robbed of valuables.

Today we take it for granted that the Thames flows cleanly and supports a range of wildlife. We also rely on disease-free water flowing from the taps and wastewater being washed away to treatment works to be sanitised. A century and a half ago today’s necessities were undreamed of luxuries. Indeed when one MP raised the issue of the stinking Thames he was told by a minister that it was not a subject the government could do anything about!

As a consequence cholera was one of London’s great killers. Four years before the Great Stink that almost closed parliament there was an outbreak of cholera barely a miles away in Soho. At the time it was thought that the disease was spread through ‘bad air’, but a local physician Dr John Snow had another theory. To test his idea that it was a water-born disease he marked all the cases that summer on a map and was able to identify a likely source – a street pump in Broad Street. When local people were prevented from using the pump the cases of cholera in the vicinity immediately declined.

His discovery proved the necessity of providing ‘pure and wholesome’ filtered water for the capital and from the late 1850s huge improvements were made to the water supply. The disposal of sewerage was simultaneously tackled and Joseph Bazalgette was the engineer responsible for designing and building a new system of pipes and tunnels to keep the city’s effluent flowing. He diverted the capital’s tributary rivers, sending them underground to act as waste conduits. He reshaped the river embankment and in just a few years had subdued London’s stench. Between 1859 and 1865 over 300 million bricks were used to construct a labyrinth of feeder channels and main sewers underneath London.

Yet one major problem remained even after the sewers were in place. Right up to the mid 20th century London homes and offices were heated by thousands of coal fires. Electricity was generated by coal-fired power stations situated alongside the river to facilitate fuel deliveries. The trains serving London’s railway termini were largely steam hauled and all of this coal burning activity produced huge quantities of soot and smoke. It penetrated every building leaving a pall of black dust. When the weather conditions were right, or rather horribly wrong, the smoke accumulated to create smog. In December 1952 a memorable and dangerous ‘peasouper’ fog descended. Not only was visibility so reduced that people couldn’t see across the street, it brought severe healthy problems. In excess of 4,000 people died from breathing the foul air. Cattle brought in from the countryside to Smithfield market were asphyxiated. The transport system ground to a halt.

This time the government quickly acknowledged it had a responsibility. The Clean Air Acts outlawed the capital’s smoke belching chimneys. The massive inner city power stations were closed. Today one of them houses the Tate Modern!

Londoners and visitors still complain that the capital is not as pristine as it might be. Despite the efforts of bin men and street cleaners, many of whom start work well before the city has woken up, a city can never be perfectly clean all the time. But public London in 2014 is streets cleaner than London of 1814 and today specialists like Starlet Cleaning keep offices and other commercial premises spick and span as well. Visit our commercial cleaning page to find out how our commercial cleaners can benefit you.

No Comment